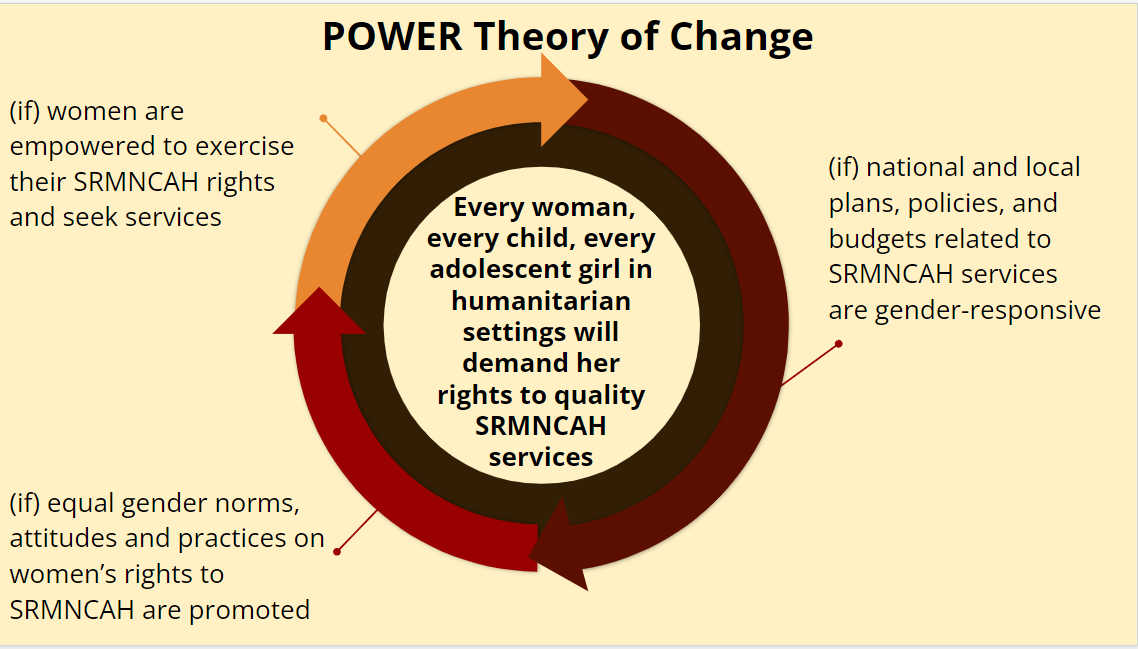

Theory of Change of the Programme

POWER contributed to creating an enabling environment for women and girls to demand health services as an essential component of achieving healthy lives and well-being for all. The POWER project adapted UN Women’s RMNCAH Flagship Programme theory of change to the context in humanitarian settings which proposed that:

- If national and local plans, policies, and budgets related to SRMNCAH services were gender-responsive;

- If equal gender norms, attitudes, and practices on women’s rights SRMNCAH were promoted; and

- If women were empowered to exercise their SRMNCAH rights and seek services;

Then, every woman, every child, every adolescent girl in humanitarian settings would demand her rights to quality SRMNCAH services; because there would be an enabling environment for women to demand SRMNCAH services.

Overview of the achievements of POWER (December 2019- June 2022)

Since POWER commenced in December 2019, the programme contributed the following towards the three results:

1. Established rights-based national and local SRMNCAH frameworks in humanitarian settings

To understand the legal and policy barriers women face in accessing SRMNCAH services, UN Women partners conducted gender barrier analyses on both regional policy frameworks and Ethiopia's national policies. Humanitarian actors in Ethiopia used these analyses to develop multi-sectoral response plans to enhance women's access to SRMNCAH services and rights and to prevent and respond to child marriage in refugee camps and host communities in the Gambella region. In Uganda, the government included SRMNCAH priorities in the National Health Preparedness and Emergency Response Plan, and the National Policy for Disaster Preparedness and Management.

Through POWER, government and civil society representatives from seven countries3 in the Horn of Africa gained knowledge and skills and shared experiences around gender-responsive budgeting to improve allocation of resources for SRMNCAH services in humanitarian settings.

POWER also brought together over 100 government, civil society, and development partners from across the region to discuss ways to advance and measure SRMNCAH commitments and women's SRMNCAH rights in humanitarian settings. This was facilitated through a four-part virtual Regional Social Inclusion and Gender Index (SIGI) Policy Dialogue organized in partnership with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Gender Development Centre.

2. Improved promotion of equal gender norms, attitudes, and practices on women’s rights to SRMNCAH in humanitarian settings

Community and religious leaders, as well as health care workers, were mobilized through POWER to increase awareness of equal gender norms and practices on women's rights to SRMNCAH in refugee camps and host communities. POWER also supported and scaled up groups of community champions for gender equality to advocate for SRMNCAH rights for women and girls.

Lack of economic independence was identified as a major barrier for women and girls to access SRMNCAH services, limiting their decision-making power and access to the financial resources required to reach service providers. In Ethiopia, women and adolescent girls were equipped with entrepreneurial skills and supported with small start-up capital to start their businesses. In Uganda, women were supported with fruit seedlings to empower them economically while promoting environmental conservation.

3. Empowered women and girls exercise their SRMNCAH rights and seek services in humanitarian settings

Through POWER, women leaders and advocates started to elevate attention for and uptake of SRMNCAH services in humanitarian settings in the Horn of Africa. Within the region, more than 50 female and male leaders and gender equality advocates gained knowledge and skills to deepen their advocacy efforts for SRMNCAH rights and services in humanitarian settings. The programme also strengthened the awareness and knowledge of women leaders to champion SRMNCAH rights and lead advocacy in their respective communities. This was complemented by community-based advocacy training, equipping young and adult women's rights advocates in Ethiopia and health workers and village health teams in Uganda with new skills for advocacy.

"I call upon policymakers to enact, enforce progressive laws and policies that promote the women and girls' enjoyment of sexual, reproductive, maternal, neonatal, child and adolescent rights and services." Azizuyo Brenda Facy, International Community of Women Living with HIV Eastern Africa (Uganda).

In Ethiopia, women's groups and networks with wide membership in the refugee and host community in Gambella region were supported to enhance their capacity and planning to improve community mobilization and dialogue on SRMNCAH priorities. POWER also contributed to women’s increased awareness and knowledge of their SRMNCAH rights and available services in health care facilities, even in emergencies. This linked woman living in refugee and host communities in Ethiopia and Uganda with critical SRMNCAH services.

To learn more about the issue and the programme's activities, please watch the below video.

Lessons Learned

The multi-faceted barriers preventing women, adolescents, and children from accessing their right to health require comprehensive and targeted actions reaching individuals, communities, institutions, and the wider society. The dynamic nature of humanitarian settings, combined with the continued COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the need for sustained investments and the critical role of partnerships in realizing change.

The Programme’s attention to data and context analysis, and evidence generation of barriers and solutions in the Horn of Africa provided deeper insight into the challenges faced by women, adolescents and girls and the institutional gaps in implementation of SRMNCAH commitments in Ethiopia, Uganda, and the Horn of Africa region. This analysis ensured the programme activities responded to the diverse needs of women and girls and could also inform future interventions.

Strong partnerships with civil society and government partners and UN Women’s presence and programming experience in each country made it possible to adapt activities to the COVID-19 and the changing political contexts in the region. The COVID-19 pandemic and political changes prompted adjustments to the approaches used to raise awareness, conduct training, and identify alternative engagement methods for realizing the intended results.

Notes